Artist Gabriel Barcia-Colombo has created a DNA vending machine that dispenses human genetic material to highlight privacy issues emerging as biotechnology makes it easier and cheaper to access information locked in our DNA.

In a dystopian future where we all have samples of our friends’ DNA, we will be able to do things like genetic engineering in the same way as we do 3D printing.

Gabriel Barcia-Colombo

The New York artist created the DNA Vending Machine with the hope of challenging people to ask more questions about privacy and who owns the material that makes us unique.

“There are a whole range of court cases that say our DNA can be used against us for anything,” explained the artist, who is also a lecturer at New York University specialising in interactive telecommunications. “We have huge pharmaceutical companies making loads of money out of DNA from people who haven’t necessarily given them permission to use it.”

Presented in a recent TED Talk, the DNA Vending Machine replaces snacks and drinks with samples of people’s genetic code. These samples can then be bought.

“I began collecting the DNA of my friends at my house during Friday night gatherings, and then furthered my collection through several scheduled open houses where anyone could come to my studio and sign up to submit an open-source sample of their own DNA,” the artist explained.

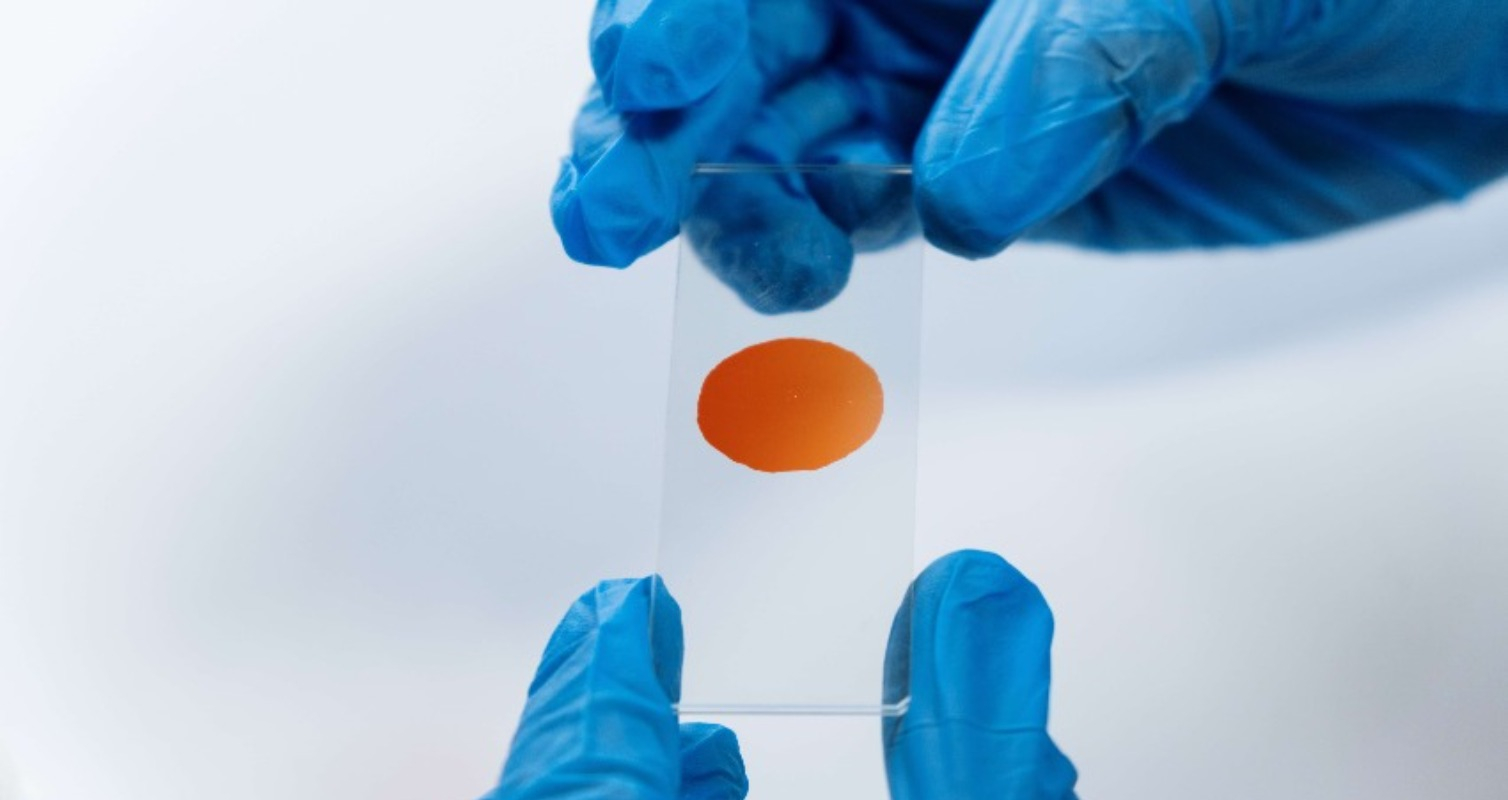

Participants in the project spat into a vial containing solution that breaks down the cells found in the saliva, releasing the DNA. Alcohol was then added, causing the strands of genetic code to clump together and making them visible to the human eye. The vials were then sealed inside identical white containers and placed inside a standard vending machine.

“Each sample comes packaged with a collectable portrait of the human specimen as well as a unique link to a custom DNA extraction video,” said Barcia-Colombo. The machine was installed in an art gallery in New York, and the artist recalls some of the reactions to the art piece. “They’re disgusted that this is using human genetic material, and they often are scared by it because the samples can be bought and used to plant evidence on a crime scene.”

Barcia-Colombo sees comparisons between DNA ownership and concerns over the collecting and harvesting of our own digital data.

Our phones are harvesting our data and then being sold is a very similar idea to companies harvesting our DNA and selling it to pharmaceutical companies without us knowing.

The DNA Vending Machine was designed to start a conversation that the artist feels is long overdue.

One of the most high-profile cases surrounding the legality and ethics of DNA ownership was the example of Henrietta Lacks. While receiving treatment for cancer of the cervix in 1951, she had a healthy part of the tissue removed without permission.

The cells were later grown in vitro and have since been used by pharmaceutical companies to develop polio vaccines and in the research of AIDS, cancer and radiation poisoning. The material is still used today and is referred to as “Hela Cells” in reference to the first two letters of her first and last name.

More recently, a court case in 1990 between John Moore, a US citizen undergoing treatment for hairy cell leukaemia and the UCLA Medical Center brought the issue back into the headlines. “The supreme court decision in the case ruled that a person’s discarded tissue and cells are not their property and can be commercialised,” said Barcia-Colombo. “It’s ridiculous. When it becomes easy to reproduce these things, it brings up a lot of personal questions about rights and you as a personal franchise.”